When Jessie Webster Cooper was desperately ill with the virus, her husband (an unemployed builder from south London) told her and their feverish son to “go to hell, and the sooner they went the better”. He would return home late at night and drunk, slam doors, swear at them, and scatter onion skins all over the floor. When she threatened to leave him, he shouted, “I will kill you if you do” and “the best place for you is to go to hell”. Unsurprisingly, Jessie was described as “suffering from general nervous exhaustion, sleeplessness, and fright”.

Jessie Webster Cooper’s experience of domestic violence in the midst of a pandemic sounds familiar to us today. Throughout the world, levels of domestic violence have skyrocketed, especially after self-quarantining, physical-distancing, and “safer-at-home” mandates were imposed.

However, the violence suffered by Jessie Cooper occurred during a pandemic that swept throughout the world one hundred years ago. The 1918-1920 pandemic – which infected 500 million people (that is, one-third of the world’s population at the time) and killed around 50 million – also saw rising levels of domestic violence. The exact number of women and children affected by domestic violence in those years is unknown. Familial violence was hushed up, divorce was considered scandalous, and only the most extreme cases of domestic cruelty were aired in court. However, newspaper reports of women seeking separation orders from their husbands regularly mention the influenza virus as exacerbating already-aggressive male behaviour due to its effect on familial finances, increased alcohol consumption, and general irritability.

Of course, the broad cultural context of the pandemic of 1918-1920 and 2020 are very different. Although the barriers to leaving an abusive husband remain extremely high today, women during the earlier pandemic faced more formidable legal and social barriers as a result of extremely limited employment opportunities for females, discriminatory property laws, unsympathetic juridical responses, and the stigma of divorce. In every country throughout the world, charging a husband with marital rape was not even possible until the 1970s (and it is still not possible in 48 countries today).

Most importantly, during the earlier pandemic, people were still at war when the virus began infecting and killing millions. They all would have experienced war-related disruptions; most would be mourning the death of a friend or member of their family. In other words, fear of contracting influenza coexisted with other imminent threats of death. And abusers were adept at exploiting such terrors. As Jessie Cooper recounted, during air raids over London, her sadistic husband took great delight in banging on her bedroom door, shouting “There’s another bomb, and another one will drop soon”. She recalled that it “used to frighten her” and her 16-year-old son “very badly”, which is why they slept in the same room.

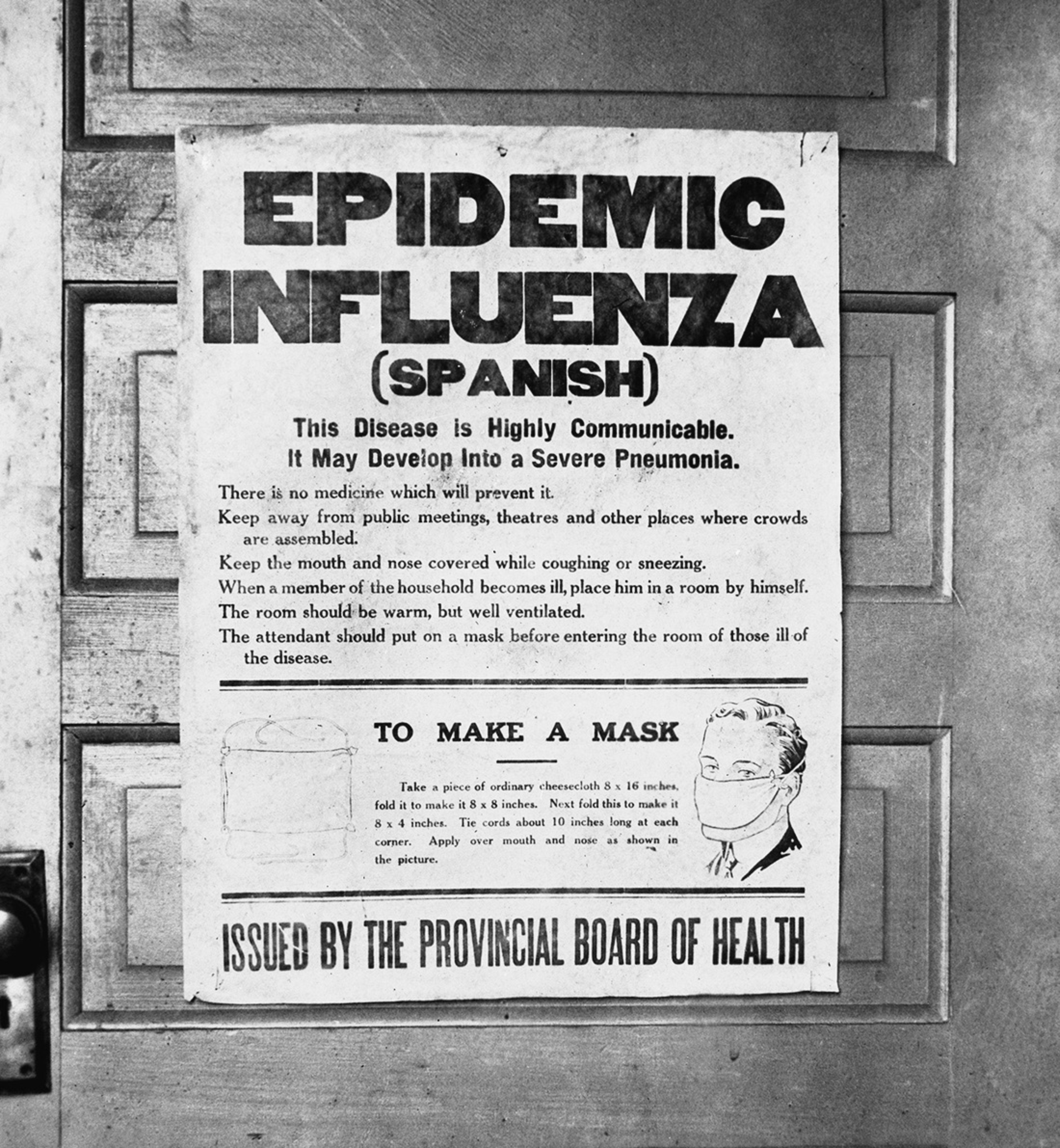

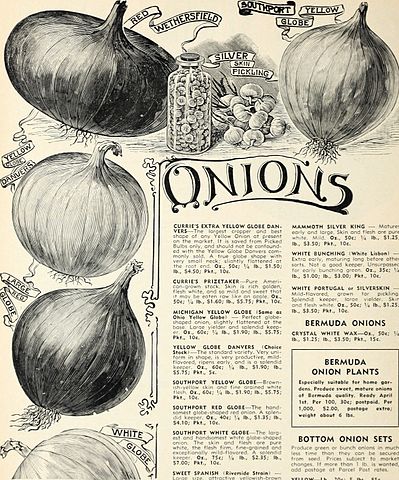

But certain contextual similarities also existed, including the lack of a vaccine which meant that preventive measures focused on repeated hand-washing, social distancing, and the closure of schools, places of worship, theatres, movie houses, dance halls, shops, and courtrooms. In 1918-1920, wearing face masks was mandatory in all public spaces in much of the U.S.: even the President wore one. During both pandemics, social gatherings were suspended, public funerals were curtailed, and city centres emptied as people retreated into their homes and other supposedly “safe” spaces. Hospitals and clinics quickly reached breaking point and public health professionals became overwhelmed by their heavy workloads. Then, as now, quackery flourished. During the earlier pandemic, charlatans advised anxious Americans and Britons to ward off influenza by eating large quantities of brown sugar, rubbing raw onions into their chests, and prolonged soaking in creosote baths.

In 1918-1920, the coercive mechanisms that abusive men employed could take different forms to what we are seeing today. For example, Jessie Cooper Webster Cooper’s husband was said to keep “his room in a filthy condition. There were onion peelings lying all over the floor”. The mention of onion skins is telling because of the belief that onions could prevent influenza infection. It was widely reported in the press that “eating of raw onions is a complete protection against influenza and indeed all sorts of evil”. Even more relevant in understanding the behaviour of Cooper’s husband was the conviction of one “distinguished London physician” that “a raw onion in a fever-stricken room soon decays, because it attracts the germs”. In other words, Cooper and her 16-year-old son had contracted influenza: by scattering onion skins throughout the home, her husband was not merely undermining her attempts at keeping the house clean, he was also attempting to “soak up” the germs that she and her son had brought into the house.

Today, as we observe the rise and rise of domestic violence throughout the world, it is useful to remind ourselves of the myriad forms that abusive behaviour can take.

Only by understanding the contexts within which violence emerges can we effectively prevent it.