First job, second career…

When I landed a post-doctoral post, my first fulltime job as a historian in October 2018 at the age of fifty, I was thrilled at the opportunity. To work as part of a research hub on sexual violence, medicine and psychiatry was a perfect fit. I could bring thirty years of learning in the public sector with me into academia. I could investigate questions that I had worried about in the years I worked in Children’s Services. Led by principal investigator Professor Joanna Bourke and supported by an amazing multidisciplinary team in a department known for world-leading research. How could I fail? I set out to answer the question – why is interfamilial child sexual abuse rarely identified by community health practitioners? Survivors say that nurses, doctors and psychologists rarely spot the signs and signals they send out, but is this a fair statement? And, if so, why?

Yes, I knew I was at risk of being overwhelmed. After all, I was leaving an environment where I felt confident that I was operating at the top of my game, while now I would be struggling to figure out the rules on a new board. It was also a challenging topic. But as well as supportive colleagues, I had plenty of transferable skills and a good training in applied and historical research so I would survive! A few months in, here are my reflections on my project and learning to date.

Research as a social activity…

My public sector experience had been mostly about planning and reviewing services for children and families and sometimes, when we were fortunate, setting up and running new services. There was always lots of research involved to find out what local people and practitioners wanted, to understand the nature of the problems to be solved, to identify the evidence base for possible solutions, to assess local and national policies, and to measure effectiveness.

I could bring those skills to my new job, always holding on to the idea of my research as a social activity carried out for the practical as well as the intellectual benefit of all participants. I would carry out the rigorous archival research enjoyed by historians everywhere. Alongside that, I would build on my professional networks in the UK and reach out to new contacts in the US. I would set up one-to-one discussions to inform the detailed research plan in terms of sources, methodology, accessibility, ethics, and relevance to contemporary practice. These background contacts would help shape my questions and contribute to establishing a list of potential informants for my oral histories.

Six months in…

When I worked in the public sector, we divvied up tasks and discussed them ad infinitum. We saw each other most days and caught up on progress. As an historian on your own project, you mainly allocate tasks to yourself. Planning is crucial so that you don’t drown in detail, lose all your scans from the archive, or forget to call back a potential source. It can be solitary and I have had to build a new routine and structure to my working life. Self-care is important: I walk, swim, and do whatever else that gets me away from the books and out of the chair.

Academic research is very different in other ways, too. In local government, every new policy or funding application had short deadlines. Swiftness was a priority. There was an acceptance that work would be fit for purpose; it didn’t need to be perfect. As a junior historian working in the context of shrinking university budgets and few tenured jobs, the expectation may not be perfection but it is certainly excellence. The exhortation is not to ‘turn something in, even if its sloppy’ but to take a reasonable amount of time to deliver high quality research, conference papers and publications. I had left my comfort zone…..

Birkbeck is a hugely stimulating environment and I’ve had opportunities to gain new knowledge and to challenge my thinking about researching sensitive topics, handling personal data, digital history, ethics and more.

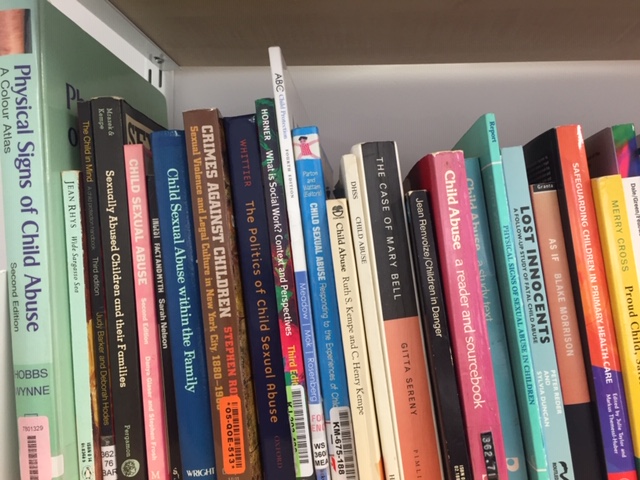

One of the risks for my project is that practitioners might not want to talk about child sexual abuse in the family because it is a sensitive topic. Not so. Five clinical psychologists, four GPs, twelve health visitors, and two paediatricians have already met with me to talk through their own careers and to help guide my research. As well as speaking very frankly about how they became aware of child sexual abuse and its interface with their careers, they have recommended reading and referred me to other relevant ideas and individuals. They were not only generous with their time but also very curious in thinking about professional responses to child sexual abuse in a different way and in its historical context. They emphasized that I should not only think about procedures and policies but also about the ways that feelings, thoughts, and attitudes affect professionals’ behaviour. I’m very excited that the oral history gathering starts this month.